figure: Portrait of J.M. Jacquard, c.1839, machine woven silk

This small unassuming image of a gentleman inventor could support the claim of being one of the most significant images in the history of computing. For it is indeed a digital image created in the late 1830s, encoded in 24,000 punch cards for a jacquard loom (Essinger 2007 p.5). It was woven by machine in an edition of at least ten, one of which took pride of place amongst the curiosities and scientific wonders collected by the gentleman scientist Charles Babbage (Batchen 2006 p.32). The subject of the portrait is JM Jacquard, inventor of the Jacquard loom, a technology that drove much of the transformation of the industrial revolution. The significance of this image in Babbage’s collection is that Babbage intuited that Jacquard’s system of punch cards could be adapted to the purpose of mathematical calculation (Essinger 2004 p.47) and is credited as the conceptual leap that lead to the development of the computer (Essinger 2004 p.48). In the context of digital photography, it is significant that a transcoded image produced by machine should be at the conceptual birth of computing.

At first glance, the development of the Charged Couple Device (CCD) technology in 1969 would appear to be the break point between analogue and digital photography. The impact of this invention was acknowledged in 2009 when Boyle and Smith won the Nobel Prize for Physics in recognition of the far-reaching impact of their invention (nobelprize.org 2009). Certainly, this is the device at the heart of the digital cameras that we use today, replacing the film behind the camera shutter.

However, the cultural imagination of the possibilities offered by digital photography has a deeper history than the invention of the CCD in 1969. A meditation on the creative implications of digital media is not a superficial engagement, but has a connection to a deeper history of human endeavour to communicate in particular ways, to express relationships, both emotional and physical, between oneself and the world.

The technological and cultural context that engendered Babbage’s development of early computing was the same culture and time that saw the emergence of photography.

In addition to the machine woven portrait of Jacquard, Babbage’s collection also included early experiments of a technology that came to be known as photography, contact prints of machine woven lace by his friend Fox Talbot, similar to that of the example below (Batchen 2006 p.32).

figure: William Henry Fox Talbot, Lace, 1845

figure: Fox Talbot, Frayed and folded gauze c1852-1858

Looking at Fox Talbot’s early experiments, it appears that he was also thinking in terms of sampling, as alluded to in digital and the example of the woven Jacquard portrait. At one point Fox Talbot experimented with breaking the image into sample points, like the stitches in a tapestry and now recognisable as similar to the grid of a pixelated image on a computer screen. Again we see the use of textiles, with Talbot employing translucent gauze to create a grid of sample points (Batchen 2011).

Another example of the ferment at this time around encoding and images is the work of Samuel Morse. A successful artist in the early 1800s, Morse abandoned painting to develop and establish the telegraph system follow the death of his wife. He did not receive notice of her illness in time to attend her funeral. Similar to the examples of digital thinking above, the dot and dashes of Morse Code could be viewed as an analogy of the 1 and 0 of the binary system at the heart of computer programming.

The idea of fixing an image from a camera obscura or camera lucida using light-sensitive chemical processes used in printing techniques occurred to a number of people in the early 1800s. Indeed, Morse had made some experiments in this direction in 1821 (Batchen 2006 p.42), so when Daguerre announced his process in January 1839, Morse appreciated the significance of the invention. He visited Daguerre in Paris a little over one month later to obtain a manual of the Daguerreotype technique. It was Morse who introduced photographic techniques to the USA when he established a commercial photographic studio later that year (Batchen 2006 p.42).

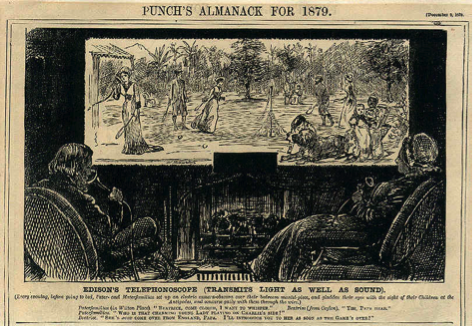

I think it is significant that Morse’s interests and contributions included image making, coding, transmission and photography, demonstrating the conceptual homogeneity at the inception of these technologies. Indeed, the possibilities of the then new media technologies were imagined in ways that we now find oddly familiar. In 1878, Alexander Graham Bell speculated on the possibilities of translating images via his invention the telephone. In 1879 Punch magazine published an illustration of Edison’s concept of a telephonoscope, an ‘electronic camera obscura’ (Batchen 2006 p.42).

figure: Punch magazine cartoon of Thomas Edison’s imagined Telephonoscope, 1897

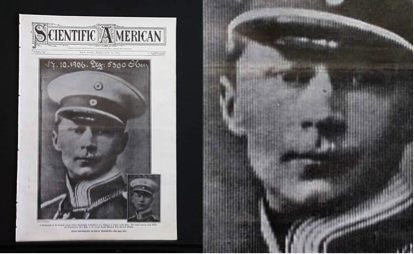

figure: Scientific American, February 16, 1907

Whilst is took a few more decades, the development of the facsimile machine was driven by the desire to transmit a dematerialised image. For example, the above cover of Scientific Americanfrom 1907 features an image sent from a distance of nearly 1,100 miles using ‘Korn’s Photographic Fac-Simile Telegraphy’.

The point of this discussion is to demonstrate that digitalisation and the dematerialised dissemination of images has a deeper history than the invention of the CCD in 1969 (Baumgartel 2005 p.61). Indeed, the technologies of photography, computing and telegraphy grew out of the same time and cultural context, their conception was intricately interconnected. We are not dealing with a radical new direction with the development of digital photography but the surfacing of potentials that were embedded at the time of their invention.

In the same way that underling the digital revolution is social and ecological destruction, so to the Jacquard loom was the technology behind the satanic mills of the industrial revolution.

Bibliography

Batchen, G ‘Electricity made visible’ in Chun, Wendy Hui-Kyong, and Thomas Keenan. New media, old media : a history and theory reader / edited by Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Thomas W. Keenan. n.p.: New York : Routledge, 2006., 2006.

Baumgartel, T 2005, ‘Immaterial Material: Physicality, Corporality, and Dematerialisation in Telecommunication Artworks’, At a distance : precursors to art and activism on the Internet edited by Annmarie Chandler and Norie Neumark , Cambridge, Mass. : MIT Press.

Essinger, J 2007, Jacquard’s Web : How A Hand-Loom Led To The Birth Of The Information Age / James Essinger, n.p.: Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2007, c2004.

Natale, S 2012, ‘Photography and Communication Media in the Nineteenth Century’, History of Photography, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 451-456.

see also Daniel, Malcolm 2004, “William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) and the Invention of Photography” New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tlbt/hd_tlbt.htm